The global community adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) last September 2015. The SDGs are not the 2.0 version of the Millennium Development Goals, which aimed to help developing countries solve their main social challenges, such as access to education or health care.

Rather, the 17 SDGs are a roadmap for all citizens, North and South, to eradicate extreme poverty and create a better world for all countries. The SDGs spell out challenges rather than sectors where progress needs to be made. SDG 11, for example, focuses on sustainable cities and communities, while SDG 13 focuses on climate action. Admittedly, the bar is set high and achieving the SDGs will not be easy.

Yet, the SDGs also put forth the way to achieve their bold agenda: by forging partnerships (SDG 17). The effort demands action from citizens, governments, civil society, businesses and the philanthropic community. Given the challenges at hand, none of these actors can solve these issues on their own with money alone, regardless of the amounts.

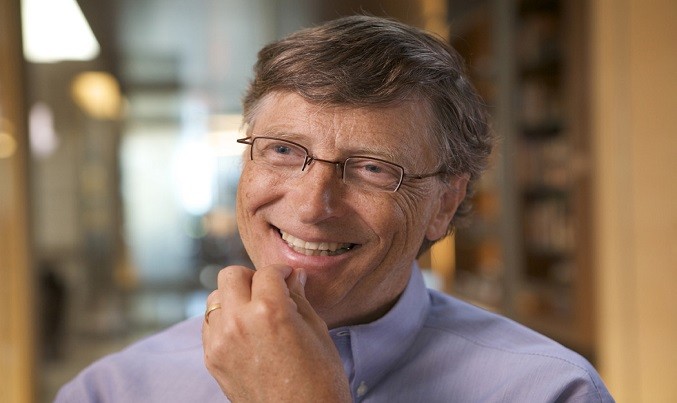

Foundations understand this reality. To address a number of areas included in the SDGs, philanthropists have given annually an estimated US$32 billion (OECD, 2014) to tackle some of the world’s most pressing development issues, such as malaria or economic and gender inequalities. But money alone is not enough to move the needle. What also counts is the additional value foundations offer through three concrete roles they play as:

Advocates: Foundations are at the forefront of raising public awareness through thought-provoking campaigns about the challenges the world faces: unclean water, no access to electricity, poor or no education for girls.

Consider the Gates Foundation’s multi-year anti-malaria strategy, “Accelerate to Zero,” adopted in 2013. It aims to develop new approaches to reducing the burden of malaria and accelerating progress towards eradicating the disease. “With and For Girls’’ brings together eight organizations–EMpower, Mama Cash, Nike Foundation, NoVo Foundation, Plan UK, Stars Foundation, The Global Fund for Children and The Malala Fund–to support civil society organizations working to improve the lives of girls and their communities. This group is developing a global awards process that will provide a total of US$1 million to strong, local, girl-led and girl-focused organizations next year.

Foundations work to advocate and raise awareness of various causes, even some less present on the public’s radar screen. This includes the Kellogg Foundation’s advocacy in fighting for racial equality, or efforts by the Ayrton Senna Institute and the government of Brazil in the Rio state to develop soft skills in education to drive success.

Innovators: While foundations support a variety of issues, they are especially well placed to test new approaches and experiment with new ideas. They are at the forefront of pushing new ways of doing things–processes, methods, technologies. They can do so because they do not face the same constraints as institutional donors, which are accountable to taxpayers or tied to the political cycle in the coun- tries where they work. Foundations are more risk-tolerant and can afford to fail and try again with relative flexibility.

The Shell Foundation, for example, took an innovative approach in helping young social entrepreneurs develop cookstoves that do not use coal. On the one hand, it supported entrepreneurs through funding, advice and help with business plans and marketing. On the other hand, it developed the sector itself by targeting the market barriers that impede the production, deployment and use of clean cookstoves in developing countries. It helped create the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves in 2010, which works to save lives and protect the environment through the use of improved cookstoves and fuels. The Alliance aims to switch 100 million homes to clean and efficient stoves and fuels by 2020.

Impact drivers: Many foundations find themselves at the forefront of gathering data and evidence to measure results and impact. Philanthropists are investing in truly understanding if what they do is making a measurable difference. Philanthropic giving is increasingly dealt with in a manner comparable to traditional investing. In other words, each dollar has to be ‘invested’ to maximize impact as if it were a productive investment. Returns are measured in social gains.

For instance, the Novartis Foundation has been monitoring impact by conducting some randomized control trials (RCTs). RCTs show whether a particular intervention does or does not work because they compare the outcomes for people who receive it with those who do not. Being able to demonstrate impact has thus become paramount for the philanthropic sector, which is exploring ways to further the monitoring and evaluation in its programs.

While individual foundations make the case for the value added of their particular efforts and the uniqueness of their approaches, the time is now to optimize philanthropy’s overall, collective contribution to the SDGs as advocates, innovators and impact drivers. Bringing foundations together to share lessons, engage in coalitions and discuss fresh ways to achieve impact at scale through all these means is critical to advancing the SDGs.